In society nowadays, bilingual kids are usually graced with the nickname of “walking dictionaries” or “born interpreters”. As a 50:50 child myself, I’m afraid to say that’s sadly not quite true. They are lucky enough to be brought up in multicultural environments and how they pick up a language by ear and progress really has the wow factor. From a young age, they do experience what could be seen as “casual” translating, whether it is by translating the Spanish menu in a restaurant for their English father or food products in Mercadona for a friend. Therefore, this is most likely why they are expected to thrive as translators in the professional word with little training but vast language knowledge. Yet there is a huge difference between interpreting in social encounters to interpreting at conferences or summits.

Bilinguals may be at a slight advantage but that is just a small head start, they are going to need training, lots of it. Becoming a professional takes its time, but in the early stages it is all about the basics.

First up, you are going to tackle unknown and complex terms, such as legal or medical, unless you have experience in the domain. Nevertheless, you are not expected to know every word, translators are always learning no matter the experience or the fluency. As a native you are not counted upon to perfectly translate a citizenship application form rich in legal terms.

Now if I was to say “multi-tasking”, you may think of when you are frying your eggs in the pan while keeping an eye on the bread in the toaster. Not this time. Juggling tasks is a skill to be mastered. Interpreters have to listen, think, speak and keep their body language in check all at the same time. Meanwhile translators have to research, write, think of the target audience and keep an eye on the tone and language. For an untrained bilingual, executing so many tasks at once will seem incredibly daunting. If they attempted to interpret, it is probable they will attempt to get every word across and panic if they cannot find the equivalent in the target language. This is why we are trained to know that it is all about getting the meaning of what is being said across successfully and avoiding the word for word trap.

Let’s have a look at the two f´s: fluency and formality. A bilingual may have executed oral fluency, but what about written fluency? Just like the rest of us, they will be used to informal writing such as chatting on social media or writing postcards, perhaps the most formal writing for them would be writing a CV or an essay. In the translation industry, they’ll have to take on criminal records, citizenship papers, birth certificates, etc; deal with different alphabets and grammatical rules, and thrive under the pressure of satisfying their client.

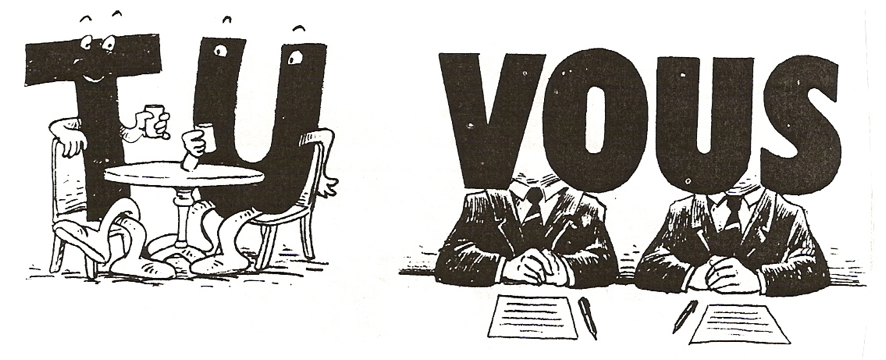

Formality is also key, translators have to take care with the tone and language by always keeping the target audience in mind and what terms are required (e.g. medical or scientific?) Bilinguals would have been brought up to speak rather informally and would have little experience of formal situations. Meanwhile in English we may not have this problem, in languages such as Spanish and French, there is a formal and informal way of addressing people which must be learnt. It is advisable to save the “tu” form for your social life and focus on the formal use of “vous” or “usted” in working environments.

All in all, we can conclude that being bilingual is not a fast track into the world of employment. If you are up against a 100% English candidate who has experience, a degree and is multilingual at a job interview, you are up against some serious competition. Translation companies may hire bilinguals, but this is because they see potential, they seem them as wannabe translators who want to excel. Here at CBLingua, we are a mix of foreigners and natives but one thing we all share is experience and love for translation and interpreting, there is no superiority just because one person may be more linguistically competent than the other.